I previously bought you information of why Jesus wasn't actually called Jesus. In a similar vein, Mouse raises the issue of the translation problem in the Lord's Prayer.

The 'Our Father' is in many respects part of the cultural fabric of the nation. Even those who never set foot in a church will likely recall the words when prompted and many use the prayer as part of their daily devotions and regular cycle of prayer.

Some still smart at the 'modern' translation, which switches 'forgive us our trespasses' with 'forgive us our sins', out of a reverence for the tradition and elegance of the King James Version. Mouse is agnostic on that issue, but it speaks to the extent to which the prayer is known and loved that it is almost the only piece of scriptural translation that can provoke this sort of debate outside of academic circles.

More recently, the Pope caused a stir in 2017 when he said that 'lead us not into temptation' is not a good translation. God would never lead anyone into temptation, so he preferred 'let us not fall into temptation'.

It is not a good translation because it speaks of a God who induces temptation. I am the one who falls. It’s not him pushing me into temptation to then see how I have fallen.

A father doesn’t do that; a father helps you to get up immediately. It’s Satan who leads us into temptation – that’s his department.

These issues, however, are what Donald Rumsfeld would describe as 'known unknowns'. We know what the Greek means and are simply searching for the best rendering into English.

It is not a good translation because it speaks of a God who induces temptation. I am the one who falls. It’s not him pushing me into temptation to then see how I have fallen.

A father doesn’t do that; a father helps you to get up immediately. It’s Satan who leads us into temptation – that’s his department.

These issues, however, are what Donald Rumsfeld would describe as 'known unknowns'. We know what the Greek means and are simply searching for the best rendering into English.

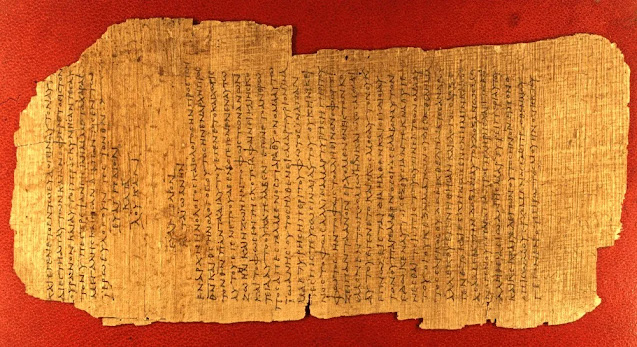

But there is a bigger problem lurking in the text. It is known as a 'hapax legomenon'. A hapax legomenon is a word that appears only once in ancient texts. Having just a single example of a word makes translation extremely difficult as we have no other contexts to which we can refer to fully understand how the word is used and what it means. And the Lord's Prayer has one. Well, technically it is a dis legomenon - a word that appears only twice - since it appears in both Matthew and Luke's gospel, but that hardly helps as they are repeating the same story in the same context.

The word in question is epiousion - this is traditionally translated as 'daily' in the context of 'Give us each day our daily bread'.

When Mouse first heard this translation issue it occurred that it is a very strange sentence construct to say 'give us each day our daily bread'. And now he knows why.

This is also a great example of the translation challenges we have with the Bible. The first translation challenge is the realisation that Jesus's words probably weren't spoken in the Greek that the gospels were written in, so the gospel writers have already translated them from Aramaic into Greek. Since this word appears in no other surviving ancient text, it is quite possible that it was coined by the gospel writers for the purpose of the prayer. Then we have the issue of dealing with the ancient form of Greek.

When we turn to the issue of how to translate epiousion several options have been offered up by credible sources.

The Tyndall Bible and the King James Bible opted for 'daily' and other translators used the same logic with a twist, such as 'bread for today'. This is based on breaking the word into its component parts - epi as “for” and ousia as meaning something like “for the being” with an implicit context of the current day. Epiousion also looks a lot like epiousei which appears several times in Acts, to mean 'next' as in 'the next day', and it has been suggested that epiousion could be a masculinised version of epiousei.

But most modern scholars reject this translation as it is just too tenuous an etymology and there are lots of examples of 'daily' in the New Testament which don't use the term epiousion.

There is an inherent weakness on relying on simply breaking the word into its components without understanding the context. Imagine a world in which the English language became extinct and only fragments were available for future translators to work with. When they read a text that said the writer was uncomfortable with the 'vibe' of something, a translator may assume that the root of 'vibe' being 'vibrations' meant that the writer was uncomfortable with the physical effects caused by something vibrating. They may have missed the Beach Boys seminal work 'Good Vibrations' which brought an entirely new colloquial meaning to the term.

Jerome came up with a novel solution when he created the Vulgate, the latin version of the New Testament. He came up with the term 'supersubstantial' (in latin supersubstantialem). This is also based on breaking epiousion into its components but coming to a different conclusion on how to translate those components - epi as “super” and ousia as “substance”. This has the blessing of the Catholic Church which believes this, or alternatively 'superessential' is the better rendering. The Catechism talks to the multiple layers of meaning this leads us to, ultimately pointing to the bread that we all need - the body of Christ.

The problem with this is that it isn't really a translation - if you are inventing a new word to translate something into, you haven't really translated it at all. The reader has to carry on the work by figuring out what 'supersubstantial' means.

Others have suggested alternatives, such as 'bread that doesn't run out' or 'the bread we need'. These are less based on a strict translation, however, and ultimately rely on a guess at what the authors might have been trying to suggest - in some ways a more authentic attempt at translation, but attempts that can neither be verified or falsified.

So where do we land? Ultimately the only conclusion we can legitimately draw is that we don't really know what epiousion was intended to mean. That may be uncomfortable, given its place in the prayer Jesus taught us, but the fact remains that we don't. We can plump for a translation which seems to carry the ring of truth about it, but that is probably the best we can do. For Mouse's part, I'm happy to stick with 'daily' and enjoy the wonderment.

The implication of this, however, is that while we should continue to study the scriptures with diligence, we must remember that they are there to point us to the one who saves, and should not become the subject of worship themselves. We should expect to continue to learn more about our translation choices as we continue to study more ancient texts, enhancing our contextual knowledge of the language and context of the scriptures and should recognise the reality that there are real challenges with translating ancient texts.

I don’t know about epiousion but I agree with the Pope about “lead us not into temptation” as I always worried about the theological implications of that. I assumed it meant “let us not fall into temptation” but it still felt weird saying it. Also the Pope’s suggestion fits the cadence of the prayer; it is still iambic.

ReplyDeleteI went a little way down this rabbit hole the last time you mentioned it on Twitter. I was vaguely aware of the Greek problem but what struck me was the Jerome business which came as a major surprise. Because, well, Panem nostrum QUOTIDIANUM da nobis hodie, right? If that doesn't come from the Vulgate, where does it come from? (The conventional English translation, daily bread, I'm guessing, doesn't come from the Greek AT ALL but straight from the Latin.)

ReplyDeleteEveryone would assume, I take it, that quotidianum translates epiousion. But does it? It clearly means "daily" or "every day" (everyday perhaps) and epiousion, as we've seen doesn't. Jerome realised this. The important thing is that he was REJECTING the already well-established Latin version - which continued (and continues) in liturgical use despite his great status, and despite the soon-established canonical status of his translation (the Psalter in the Book of Common Prayer likewise predates the King James version, which is the best parallel that I can think of).

As far as Aramaic goes, there seem to be at least 3 versions in Syriac - which, if any, can claim originality is a question I'm not qualified to address, so I'm not even going there. But I will briefly mention the famous reference by Papias about Matthew originally writing his gospel in Hebrew (or maybe Aramaic). This seems to be a garbled memory of Q, which the historical Matthew might well have written (even though he certainly didn't write the gospel we have) - after all, someone was presumably writing down what Jesus said, and Matthew is the most plausibly literate of the Twelve. But I doubt he wrote it in Greek.

My suggestion then, for what it's worth (not much) is that epiousion was an attempt either by the translator of Q or the writer of Matthew (which Luke copied) to make the original Aramaic more theological or profound, but that parallel to that Latin-speaking Christians were already using their own more straightforward translation of the recorded words (in Q?). Which ironically makes the traditional English form of words CLOSER TO JESUS than the Gospel of Matthew. Gosh.

Thanks Nelson. I love the theory, although I think it will take a better scholar than me to evaluate it.

ReplyDelete